Memories of Yeye | Singapore | 2015

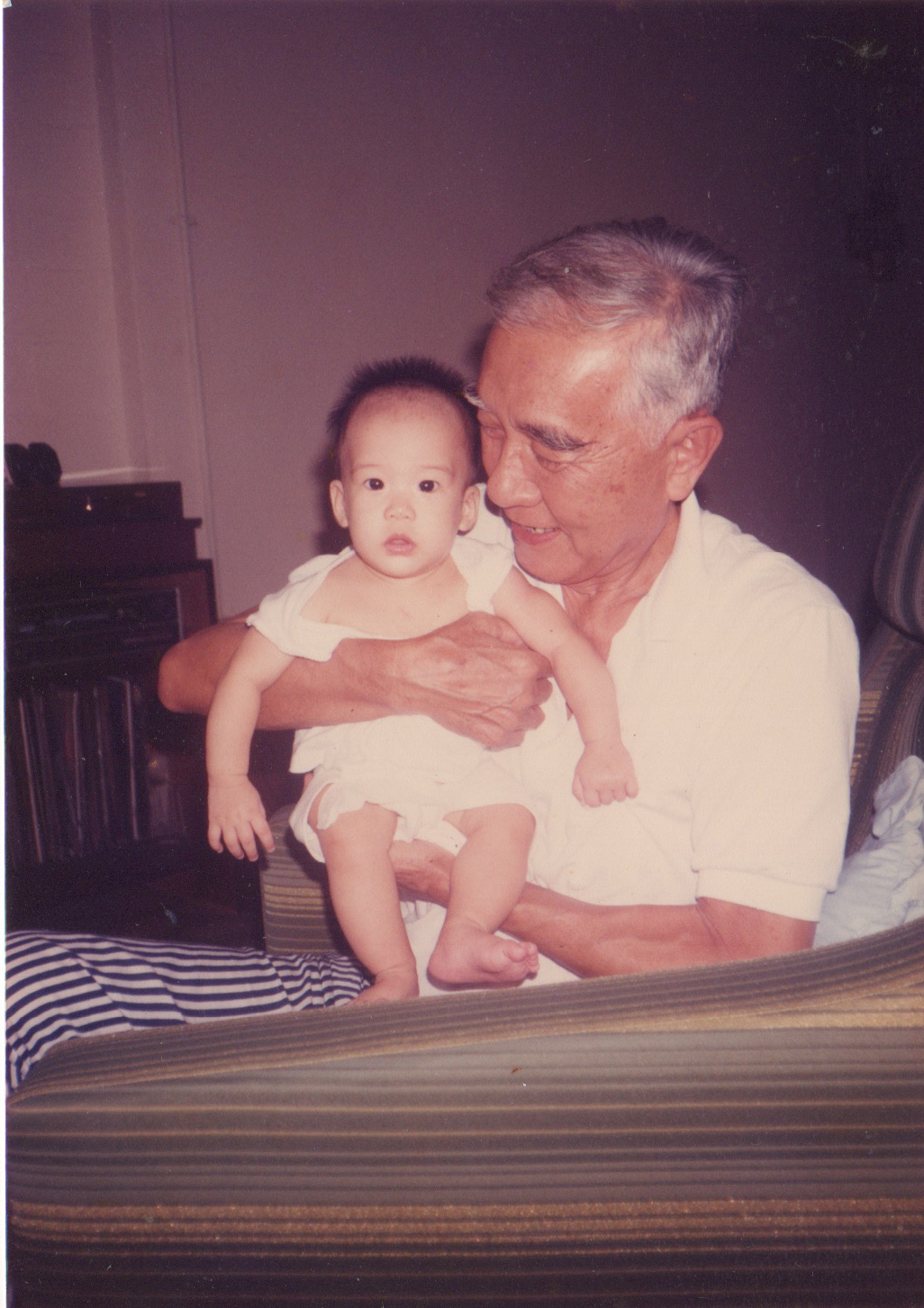

My father's father - we called him Yeye - was and is one of my favorite people.

When I was in lower primary, my school was a 10min walk from home. Yeye lived with us and would pick me up from school everyday. At the time, low coconut trees would line the sides of the street on our walk home and I had an obsession with being an explorer.

Yeye would walk next to me while I ‘waded’ through the forest of my imagination, parting the low-hanging coconut leaves and taking exaggerated steps above the ‘tall’ grass. Yeye would never laugh at me or hurry me along and when we got home, he would make me the most delicious glass of iced Milo, with lots of ice and too much sugar.

Evidence of my explorer aspirations in Maryland when I was 10.

Yeye had the straightest back of anyone I had ever known. He was also the tallest man with the bushiest eyebrows in my 8 year-old world. I asked him once, “ Yeye, how do you get such a straight back?” He smiled and said, “Just sit up straight.” And I have, ever since.

Yeye was a prolific gardener. We used to have Rambutan, Starfruit, Mango and Chiku trees around our house, in addition to lots of bouganvilleas and cacti. He also had this thing about catching rats and drowning them. Anyway, I remember my dad having a phase where he would lock my sister and I in our room on weekend afternoons to make us take naps. That was also the time when laundry would be done and the washing machine would be humming and pushing out soapsuds just outside my window. I felt I was too old for naps, so after 15mins or so of being under ‘room’ arrest, I would climb out the window, play in the soapsuds, then go round to the back of the house where I’d sit and watch Yeye trim the Rambutan tree.

He was also an amazing chef. Hainanese men have a reputation for being great at cooking and he didn’t disappoint. I would sit in the kitchen often watching Yeye make dinner. The heat would be higher for vegetables and lower for meat so I learnt to recognise the different sounds the wok makes at different temperatures.

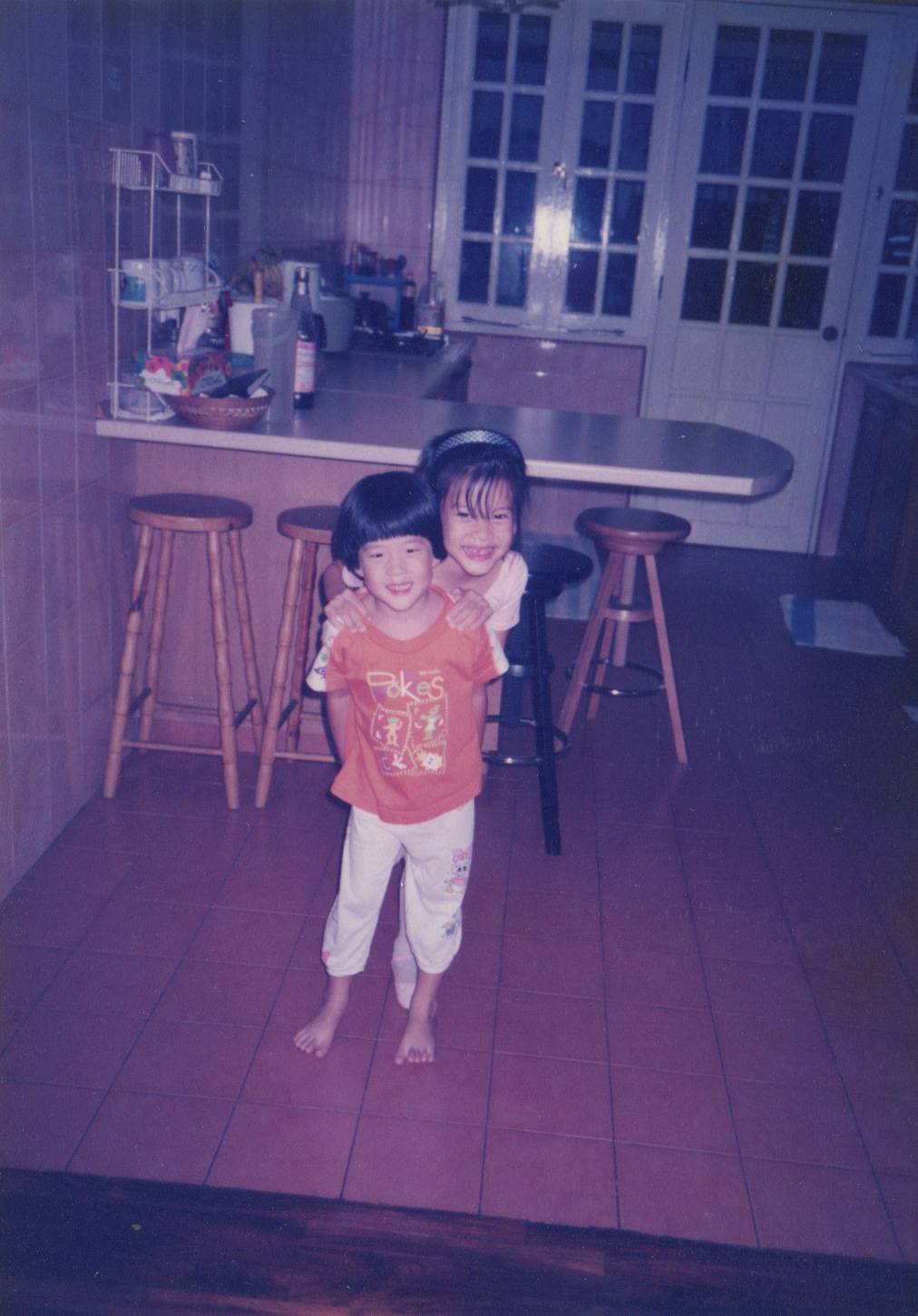

In the kitchen where I watched Yeye cook.

Yeye would sometimes take me to the wet market, this magical place with too many people and too much fishy water on the floor. I used to hold onto the back of his shirt so I wouldn’t get lost. Sometimes Yeye would buy these live blue Flower Crabs. He would take them home and put them in the sink. On one of these occassions, he flipped one over and stabbed it with a metal chopstick at the tip of the V shape part of the crab. The crab’s legs and pincer moved around for a bit, but stopped shortly after, then Yeye pulled open the V shape part and the crab just unravelled. Then he asked me to try. That’s when I learnt how to kill a crab.

Yeye could speak Hainanese, Teochew, Mandarin, Malay, and English. He taught himself to read and write English. He had the most beautiful cursive I have ever seen and only wrote with a fountain pen. He read the newspaper with a magnifying glass and I used to borrow it to try to set the grass on fire with the sunlight.

He was diagnosed with Esophagus Cancer in 1998 when I was 11. Once when he came back from the doctor, he lifted his shirt to show my sister and I the purple markings the doctors had made on his chest. I didn’t understand what it was, but he made it seem fun that he went to the doctor and got drawn on.

There was one evening I remember clearly. The first time I felt that angels were real. Yeye was resting in his room. He was too weak to eat with us, to cook, or to garden anymore, and going to the washroom wasn’t easy for him. My dad was having a cigarette outside and we were eating our dinner not too far away from Yeye’s room. All of a sudden, I felt this sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach and then a ‘thought’ came to me - “Check on Yeye. Something isn’t right.” I leaned my chair over to the edge of the table so I could see into his room, and I saw him with both hands on his throat, gasping for air. He saw me and mouthed, “I can’t breathe.” Every hair in my body stood up. I ran to my dad outside yelling, “Yeye can’t breathe! Yeye can’t breathe!” My dad ran in and started rubbing his back down while my mom called the ambulance. After that, he needed to be hooked up to an oxygen tank, which he said tasted weird.

The dining table where we had our dinner is in the back of this picture – on the left.

Yeye had a line for his grandchildren as he patted us on the head – “you are Yeye’s good girl/boy.” It was this repetitive yet reliable phrase that always made me feel loved. I don’t remember the first time he said it to me, but I remember the last. It was the morning of a school day and he was sitting in his lawn chair watching the sunrise. He told me I was “Yeye’s good girl” and I should “study hard.” He said some other things I couldn’t remember, and as I heard his words tying my shoelaces, tears were streaming down my face and I knew something was going to happen that day.

At his funeral, a three-day Taoist ceremony where we burnt paper money for him to receive in the afterlife, I remember the casket had a clear glass case over his face. I would go over there and look at him, upset first of all that they parted his hair wrong and combed it in the wrong direction. Also, his cheeks were too pink, his lips were too pink, and they pulled his face into a kind of smile that was unnerving to my 12 year old self. Nevertheless, I would look at his face and say with my sincerest inside-my-heart voice, “Yeye wake up. Wake up. Wake up and we can go home.” I willed him to open his eyes, but it didn’t work.

I didn’t cry at his funeral. I think I was numb, but I told myself he said goodbye to me the day he died so that’s why I was ok. But on the day of his cremation, seconds before they put his body in the oven and all of us were behind this glass wall, I felt a sudden rush of questions – What if I forget how his face moves when he’s happy or sad? What if I forget how tall he is, the sound of his voice, what he smells like, what his hand feels like? I felt swallowed up by tears and basically burst into a wail that scared me. So I buried my head in my mom’s tummy. As soon as the rush came, it left.

I’m in the centre on Yeye’s lap.

It’s been over 15 years and I have forgotten all those things, but I’ve never forgotten what it felt like to be loved by him. So every few years, I look back on his letters from a time before I was born and for the few years we were in D.C. and I have a good cry, grateful that I knew a love like that.